I’ve been researching how to approach teaching about mythological monsters for a few months now, and I have some good ideas about introducing them–Grendel, Polyphemus, and Count Dracula all have a place in my reading list.

I’m still working out how to teach the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, though. I’ve been working on a series of poems about these figures for a while now, so I definitely have a personal interest. Once upon a time a friend of mine gave me his favorite writing exercise–write a poem that scares you. I guess I’ve been working on this Minotaur series ever since then, and it’s been a good long time.

Here’s a poem I wrote a few summers ago about the beast. I’ve derived some of the ideas from mythological research (for example, his name–Asterion–is frequently cited by many storytellers) and some I’ve made up myself.

Son of the Stars

Those not in the know assume Pasiphae

had a natural sense of irony, god-warped,

hyperbolic, when they hear his name:

Asterion, son of the stars. But it was in the ninth

midnight of the ninth month since he was

put inside her: nine hours of pushing,

nine midwives in attendance, and one

who fainted when he finally emerged

and, running a white cloth over his forehead,

she felt the nubs that would become his horns–

it was a cold black midnight,

one where the Milky Way was a scattering

thick, almost, as Cretan sand, and each

particular star glimmered, a thousand

wet eyes watching. A midnight where

anyone mortal and awake might look out

and say: this is the true nature of things,

the world as it was meant to be–still,

unclouded, stark, with nothing in the air

to muffle her cries, or those first tentative

furious bleats of her newborn son.

Later, the queen’s breasts would swell

to the size of udders, and the last of the god’s

punishment would flow out of her.

Weighted, exhausted, she would feed him,

hours at a time, and when he slept

she would shift her enormity to the window,

draped in wet silk, breathe the cool air

and wait for the next cry. What would wean

him, send Minos into the nursery, to step

over the splinters of the door, to tear the child

from her arms, to send him in a clumsy bundle

to the royal paddock, to drink from his herd:

her cry, thin, rasping, and defeated–

it’s my blood, my blood, there’s nothing else left.

But soon this, too, would be insufficient.

The teeth that poked through those flat bovine gums

were not the cud-grinding molars of his father,

but, almost human, an ape’s fangs,

outsized, meat-tearing, as if designed to slice

through his thick tongue again and again,

whetting his thirst for humiliated rage.

Minos would go to the stable nightly,

not knowing what to hope, and sit with him,

where he was sometimes tied,

dressed in princely finery as out of place

as the teeth in his mouth.

Speak, he would say. Find words.

Father. Fingers. Hand. Please.

But none ever came. Only glances.

Stare-downs. Deep flared breaths.

Nothing human about this monster,

Minos decided. No son of mine.

But this is where he was wrong:

It was what was human about Asterion

That made him a monster at all.

His thumbs, his memory, his ability to imagine

The stars outside the stable walls

Tumbling, the voice of the constant sea

A sigh, a groan, the sound of his father laughing

Through a closed and unopenable door.

I’d never thought much about why exactly the Minotaur scares me. Certainly, lurking in the darkness of an unsolvable maze is pretty scary, and a bull preying on human flesh is equally unnerving. But in my gaming days the race of minotaurs always seemed kind of cool, almost noble, and never monstrous. The Narnia films do a great job of capturing the D&D style minotaur, with their elaborate armor and Klingon-y sense of honor and whatnot.

I guess Ray Harryhausen’s only shot at a Minotaur was a little more frightening–the stop-motion Minoton from Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger was pretty awesome in his robotic silence. He could also row a boat like nobody’s bidness. He didn’t do much in the way of action, and he certainly didn’t have any personality, but he was cool. His death–plopping into the ocean–was ignominious at best.

In Terry Gilliam’s awesome Time Bandits, though, the Minotaur kind of makes an appearance. He’s named by Sean Connery’s Agamemnon only as “the enemy of the people,” and his bull head seems more mask than body part, but as scary monsters go, this one is pretty wicked. He also makes some hideous screams and grunts before Sean finally does him in.

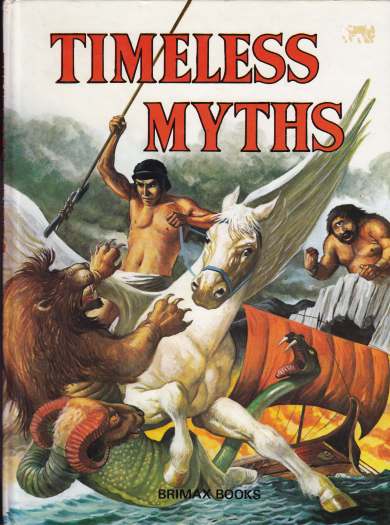

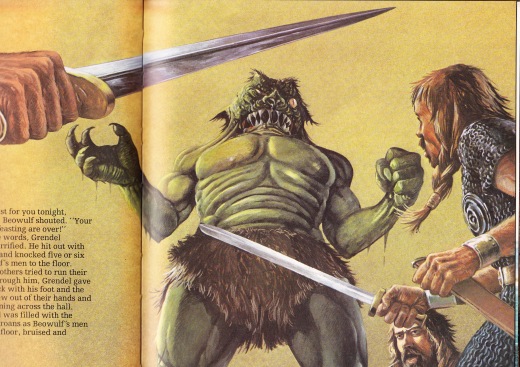

My last post detailed the images of Grendel in Brenda Ralph Lewis’ 1980 book Timeless Myths. Again, illustrator Rob McCaig managed to create an image that burned permanently in my mind as the definitive Minotaur.

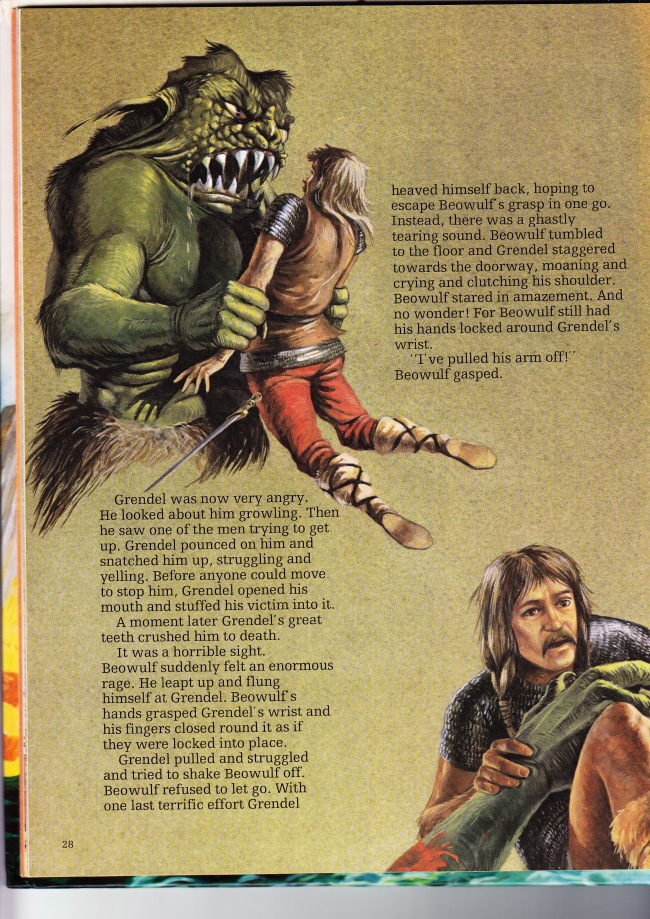

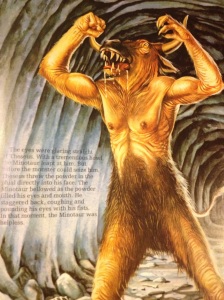

Tell me this doesn’t scare the crap out of you. The best Minotaur, from Timeless Myths. Painting by Rob McCaig.

I mean, look at the horrible glowing yellow eyes, the smelly-looking hair, the predatory, slavering teeth, the horrible pasty skin, the multiple drool ropes–this thing is definitely what lurks under the bed or in the closet once the lights go out. I imagined it making some pretty horrible sounds as well, and had a hard time staying on this page when I read the book.

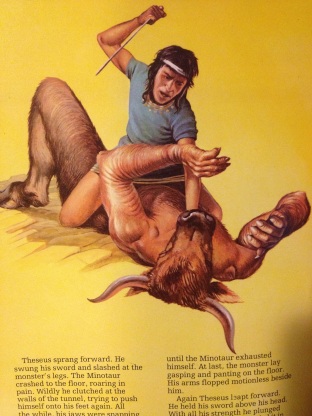

As Theseus prepares to deal the fatal blow, ol’ Asterion doesn’t look so vicious. I guess it’s the view. Painting by Rob McCaig.

Of course, no monster myth is complete without a hero, and when Theseus finally makes his move, McCaig’s painting shows the Minotaur to be more helpless, more calf-faced, more King-Kongy than the previous image. The text doesn’t do the monster any credit, but the painting made the story a bit more ambiguous. David D. Gilmore, whose book Monsters: Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts, and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors I’m reading to prepare for my class, would approve. “I have always believed,” he writes, “that the endless fascination with monsters derives from a complex mix of emotions and is not simply reducible to the standard Freudian twins of aggression and repression…the monster stands for both victim and victimizer.” I think this children’s book shows Gilmore’s thesis in spades.